Can tulips that once cost nearly a million dollars a unit shed light on recent developments in the world of private equity and enterprise valuations over the past two decades? Or explain why the rule of 40 is no longer enough to measure the vitality of an organisation? While this article looks at private equity and how company valuations have changed over the past few years, our story begins with… tulip bulbs. Stay with me, you will understand why very soon.

Between 1634 and 1637, during the Dutch Golden Age, there was an incredible craze for tulip bulbs.. Day after day, the interest in this flower was growing, and the most beautiful specimens were snapped up at ever higher prices. The market went completely crazy and the value of the bulbs lost all rationality. At the peak of tulip mania, in February 1637, some single tulip bulbs sold for more than 10 times the annual income of a skilled artisan. Imagine: a bulb, a single small bulb of this flower, could be exchanged for a horse, and the most beautiful of them, for a house, the equivalent of 1 million euros at present!

Obviously, this irrationality ended when, one day, one merchant started hesitating, another one had trouble finding a buyer following an (expensive!) acquisition. Very quickly, the price of the tulip bulbs collapsed, even faster than it flew away.

The parallel between what happened almost 350 years ago and what is happening today in the world of venture capital is striking: start-ups have been seen as the next big thing, especially internet companies. And the numerous amazing success stories we all know justify it. But this led to some of them being valued and traded based on the sheer potential of their growth, often ignoring the fundamentals that underlined their true value. Just as happened with tulip bulbs, these businesses were bought and sold at higher and higher multiples of their revenue. This runaway growth bubble recently became unsustainable as cash became increasingly scarce and organisations were unable to meet the costs of growing.

It is undeniable that the risk inherent in investing in companies with strong growth but burning considerable cash has not been sufficiently factored.

After having left the world of the rational and experienced company valuations completely disconnected from reality, we have now (or should I say: we will soon?) returned to the world of the rational, where company valuations are linked to their (real!) capacity to generate cash. Private investors have now become much more aware of the company’s vulnerabilities, leading them to change the way they assess an organisation’s investment potential. If pure growth was once considered the most important element to take into account in a valuation, it is now crucial to focus on what really matters: growing, yes, but growing profitably and sustainably.

The landing is hard…deadly for many start-ups…but it was expected and it’s definitely healthy.

The comparison between the current bubble burst and the tulip mania has its limits though. The speculative bubble experienced in the past two decades was not based on a simple fad. Contrary to what happened 350 years ago, the evolution of the valuation of companies responded to a certain logic. This logic is certainly questionable and it is undeniable that the risk inherent in investing in companies with strong growth but burning considerable cash has not been sufficiently factored. But the fact remains that there is a business “rationality” behind it. That was not the case in 1637.

And this is the purpose of this article: to try to explain the evolution of the factors which made the “attractiveness” of a company and the changes in the logics which were used for the evaluation of companies.

This article is primarily intended for curious people outside the world of Private Equity, Venture capital, SaaS world, who hear regularly about valuation, ARR multiple, churn, Rule of 40… without always understanding what people are talking about.

So much for the introduction. It’s time to share the timeline of events.

The "Growth-at-all-costs" Model

Back in the beginning of the new millennium, the dominant belief in Silicon Valley and beyond was quite clear: grow at all costs. The business landscape was filled with stories of companies that seemed to grow overnight and that soon rose from startups to tech giants and became the biggest players in the market. Google was one of those companies, who quickly saw an exponential growth by being one of the first startups to surf the internet wave in a time where it seemed like no one was paying enough attention to it. Stories such as Google’s set the precedent and, soon enough, it became a model others wanted to emulate.

That model of “first-come, first served”, drove businesses into a frenetic expansion race. The ultimate goal? To seize as much market share as quickly as possible, ensuring they remained the indisputable leaders in their domain. It became a high-stakes game, and in the famous words of Abba, a game where “the winner takes it all”.

Private equity firms had a role to play in inflating the unchecked growth balloon. Armed with endless amounts of funds to offer, they injected them into startups, often overlooking the fundamental metric of profitability. Growth metrics such as the number of new obtained clients or the speed of market share acquisition took the front stage, even if they didn’t provide the full spectrum of the company’s situation. This mindset paved the way for the investment bubble that we observed over the past half-decade, where investor criteria drifted from realism into the realm of speculative fiction.

At the time, companies that were initially acquired by private equity firms at a valuation of four times their revenue were, in a short amount of time, sold off first at six, then eight times their revenue. This “multiplication effect”, one might call it, saw the valuation multiplier skyrocket, but, at the same time, it also witnessed the very revenue on which these multipliers were applied, inflated. If we consider a company that was valued at four times its 10 million euro Annual Recurring Revenue (ARR), so 40 million, that means that in just a few short years (because revenue increased to 20M and multiple increased to 8x) its valuation might leap to 160 million, based on the heightened multipliers.

Private equity firms had a role to play in inflating the unchecked growth balloon. Armed with endless amounts of funds to offer, they injected them into startups, often overlooking the fundamental metric of profitability.

In this world of tech where prosperity seemed to be the keyword, hundreds of startups started to take their first steps. They would, eventually, become some of the biggest giants in the world of tech. Uber or even Airbnb are a part of that list, and even though they were both founded right in the middle of a global crisis (Airbnb in 2008, Uber in 2009), they thrived. For quite a few years, life was good in the world of technology. All these companies had to do was grow.

But, as it happened with the tulip bulbs and all other speculative bubbles, this one soon met its fate, as the pace at which these valuations grew became unsustainable. Businesses couldn’t keep up with the expectations set by these inflated numbers and, soon enough, cash flow issues began to emerge, leading even the biggest giants in the industry to sense a disturbance. Companies that were once perceived as indestructible in the industry, like Facebook, faced the tidal waves of the inflation bubble.

The sky-high valuation multipliers plummeted as swiftly as they had risen, with the financial community finally grasping all the inconsistencies in the “growth-at-all-costs” model. The real costs of this unrestrained growth began to rise to the surface, as many organisations found themselves burning cash at an alarming rate, without the anticipated growth that could, eventually, balance it out.

Bursting the inflation bubble and the rise of the Rule of 40

Soon enough, this financial tumult showcased the fragilities of the unchecked growth approach many companies adopted during the inflation bubble. The elevated valuations, supported by ever-increasing multipliers, masked the truth of financial instability for many organisations. This unsustainable environment soon led to a crash, as the market became overflown with companies that kept on making promises they were unable to keep. The inflation bubble finally burst and companies started facing multiple financial challenges, leading to massive layoffs and with some companies even filing for bankruptcy.

The market soon realised that the discrepancies between company valuations, growth rates, and real-world profitability needed a more grounded and balanced financial metric. One that would allow for the private sector to truly determine the health of a software company. Enter the Rule of 40, which was first introduced in 2015 by venture capitalists Brad Feld and Fred Wilson. At the time, Wilson wrote that, until then, he had never seen ” growth and profitability so nicely tied together in a simple rule”, and that the Rule of 40 was a great way to tie together two very important metrics to truly determine the health of a company: growth and profitability.

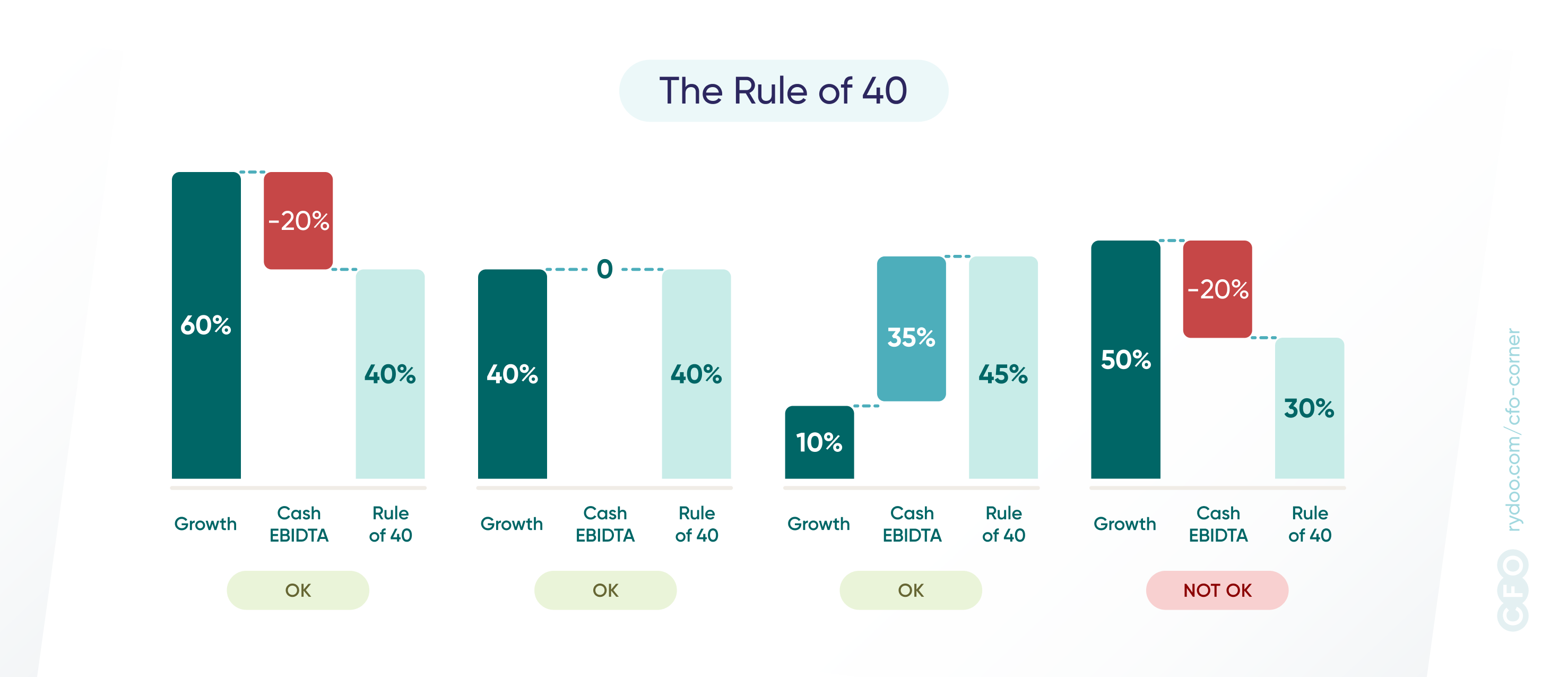

But what is this Rule of 40? It’s the perfect blend and balance of aggressive growth and fiscal responsibility. It stipulates that, when combined, a company’s growth rate and its profit margin should be, at least, 40%. This means that a company that’s experiencing rapid growth can justify higher spends, whilst one with slower growth should have higher profits.

To clearly understand this, let’s consider a company with a 30% yearly growth rate. According to the rule of 40, this organisation should maintain a profit margin of, at least, 10% of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA). On the other end, a company surging at an 80% growth rate could afford a 40% burn rate, and it would still align with the principle set by the Rule of 40.

For investors in the private equity sector, the Rule of 40 provided a clear indicator for a company’s health and future potential.

The Rule of 40 allows for a multitude or varying business scenarios. So, a firm that has achieved break-even but is still growing at a 40% rate aligns with the rule, which only emphasises the importance of growing at earlier stages. On the other end, if a company is growing at 20%, it means that it should, in theory, have a 20% profit in order to hit the 40% mark, highlighting the importance of striking a balance between financial efficiency and moderate growth.

For investors in the private equity sector, the Rule of 40 provided a clear indicator for a company’s health and future potential. And while it started as a guideline, it soon became the standard. In an environment where cash became a precious commodity and scepticism around over-valuation grew in the aftermath of the inflation bubble, the Rule of 40 turned into more than a guideline: it became the symbol of prudent financial strategy.

However, the way the private sector interpreted this rule has seen some changes throughout the years. When the Rule of 40 was first introduced, it was still heavy on growth, but it underscored instances where aggressive growth wasn’t always beneficial, especially when it came with disproportionate costs.

But the winds of change still had some tricks up their sleeves, and the market soon had to brace itself and adjust for the shift that the beginning of the 2020 decade would bring.

The pandemic shift and the acceleration of digitisation

The COVID-19 pandemic at the end of the decade brought unexpected challenges on multiple levels. Not only did it have a social and political impact, but it also led to a shift in the market from which we’re still sensing repercussions today.

As lockdowns started all over the world, the investment market came to an abrupt halt. Uncertainty ruled the world, there was no way to predict what would happen in the months that followed, and thus, investors became a lot more cautious with their choices. But amidst the uncertainty, one thing was certain: in an era where face-to-face interactions were scarce, digital solutions were no longer a luxury, but a necessity. And the investment market soon realised it.

As businesses tried to find solutions to adjust to a world where sharing an office was not a possibility, adoption of digital tools and platforms surged. And this affected not only the corporate world, but even customer behaviours. Online shopping was on the rise, digital payments became a safe way to avoid exposure to the virus and remote work became the norm, resulting in a push towards digital transformation across industries.

During this time, Software as a Service (SaaS) and subscription-based businesses emerged as the ideal solutions, with the necessary agility and infrastructures to meet the demands of a market that was trying to adjust to a new normal. As the world shifted to digital solutions, these companies, which had already been establishing themselves in the digital sector and possessed solid foundations, experienced unprecedented growth in just a few months.

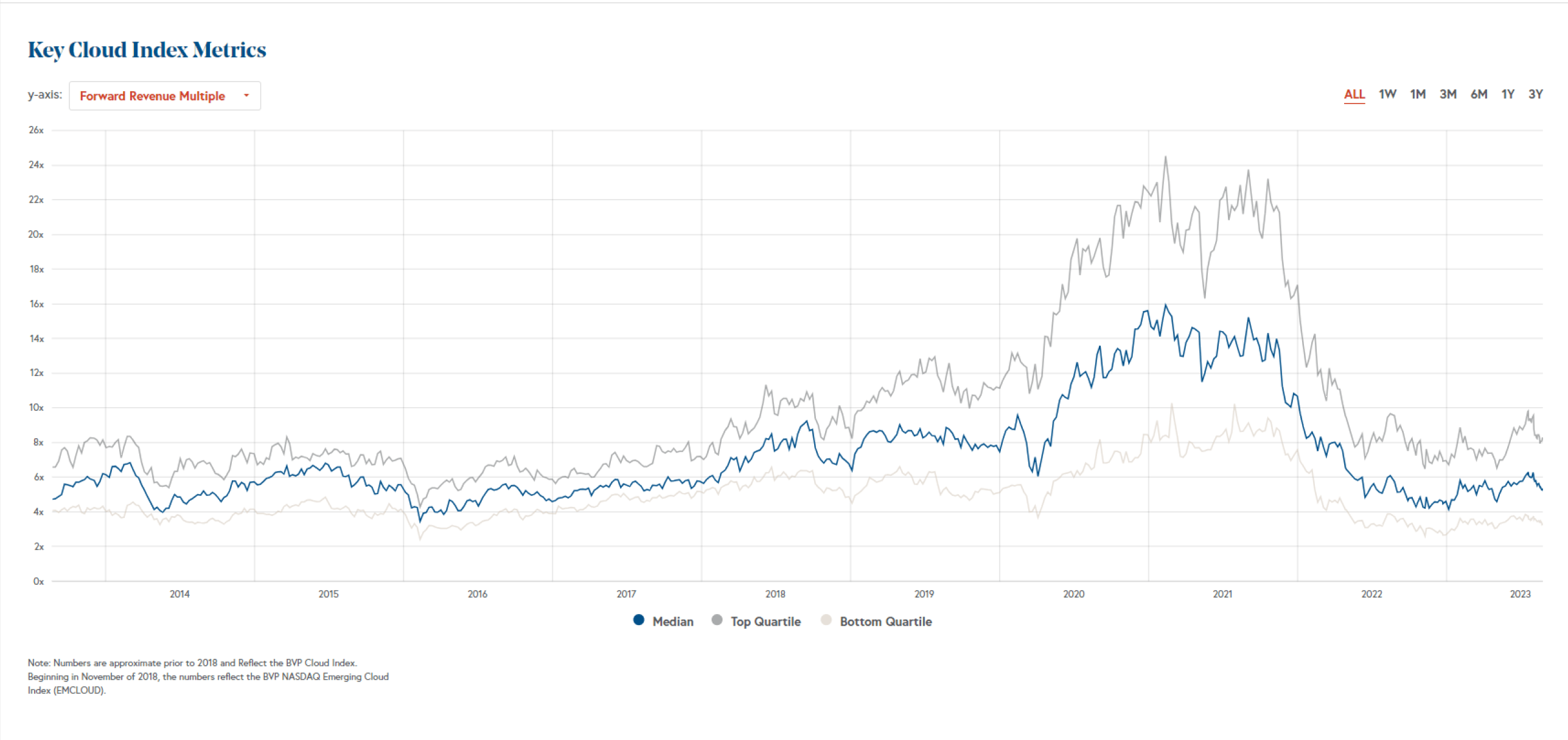

What used to be a journey of multi-year growth benchmarks was now achieved in just a few months, as these companies’ tools became indispensable, especially to facilitate remote work and customer relationship management. This led to skyrocketing valuations, as investors understood the immediate value and relevance of these businesses and anticipated their growth: The average multiple applied on the Annual Recurring Revenue – which is the most standard way to estimate a company valuation in SaaS — moved from x8 to x15 between January and December 2020, as shown in the chart below.

And while the world worried about the pandemic health implications, its social effects and witnessed the crumbling of some elemental infrastructures, SaaS companies and subscription-based models, with their consistent revenue streams, scalability, and adaptability, surged ahead. As these digital enterprises thrived, showcasing their potential and resilience, the race to acquire users and expand market share intensified. But not without its consequences.

The Crash Strikes Back and the Advent of Sustainable Finance

History has a way of repeating itself, and whilst companies saw a surge in their growth during the time the pandemic hit, the reality is that they often did it at the expense of solid foundational principles and clear paths to profitability.

The pressure to acquire more and more users and expand market share intensified, and it led many to overextend, inflate projections, and accrue debt. This unchecked growth, reminiscent of previous market bubbles, soon revealed its vulnerabilities.

As soon as life began returning to normal in the post-COVID era, the world found itself facing a new set of challenges that highlighted the fragility of this uncontrolled growth. The initial boost from the pandemic’s digital acceleration boom began to taper off, as several organisations, particularly subscription-based companies, failed to meet the aggressive growth goals they had once found so easily achievable. Investors’ confidence in these companies soon diminished, as the difference between the projected growth and the actual performance these businesses had to show became more palpable.

Profitability became the watchword and investors are no longer seeking for just growth.

At this time, the market shifted once more. Along with the effects of the global pandemic, which led to a tighter cash market, meaning less liquidity for investments, the intensified competitions, especially from emerging markets such as China, put even greater pressure on companies to deliver. And whilst the beginning of the pandemic had seen a rush of investments in the SaaS sector, the subsequent failures that arose in the aftermath dimmed the market’s enthusiasm.

Other global events also affected the market at the beginning of the 2020’s decade such as the Ukrainian conflict, which added another layer of uncertainty to an already delicate moment. This geopolitical event, coupled with the effects of the pandemic and spurred inflation, led central banks to raise interest rates. The higher costs of capital became a reality not just for the individuals, who saw a rapid increase of housing loan rates, but also for enterprises. In the private equity domain, Limited Partners (LPs) — the entities lending money to private investors — also began to restrict their cash flows whilst, at the same time, raising their interest rates.

At this time, three years after the global pandemic hit, and as investors now become more and more cautious with their investments, companies have no choice but to restructure. The aggressive growth strategies of the last three years are no longer viable, especially as costs continue to rise.

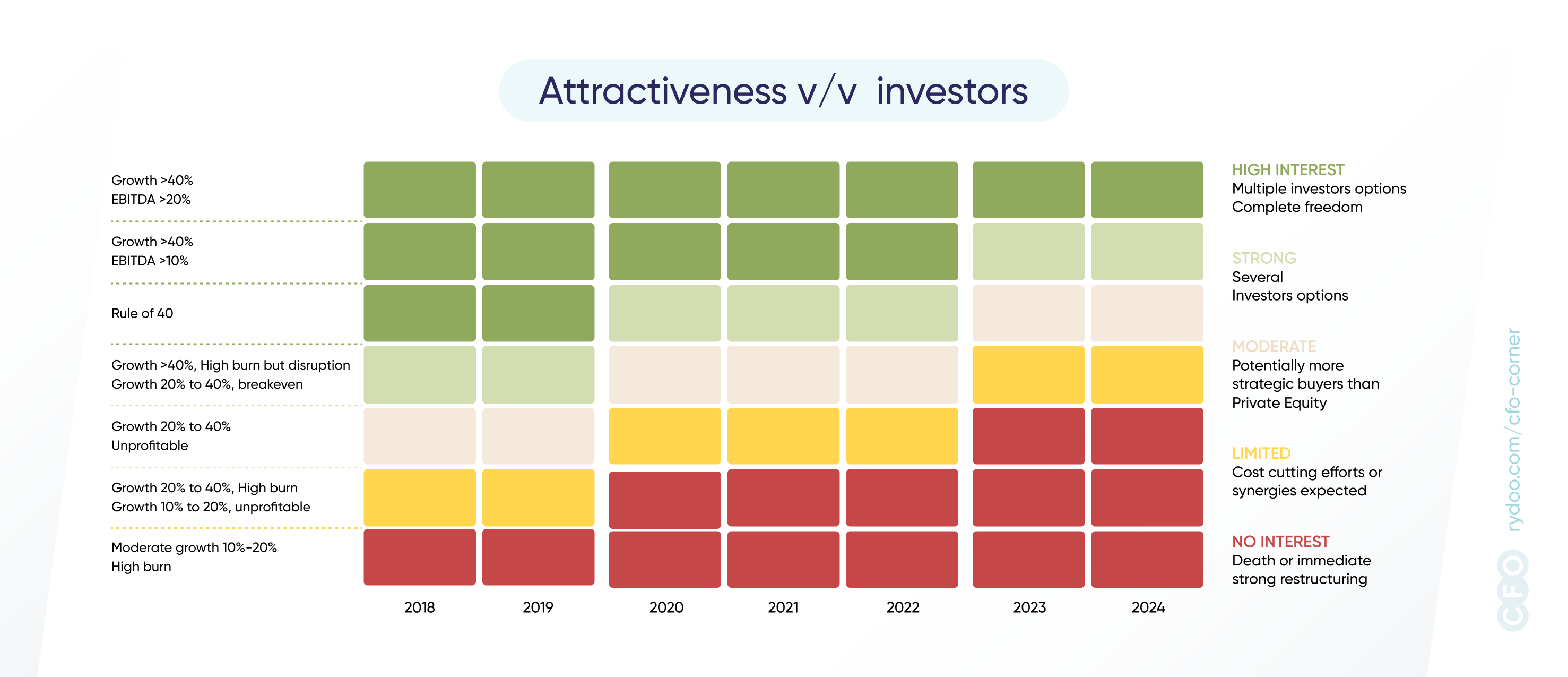

The investment narrative has been changing, yet again. Profitability became the watchword and investors are no longer seeking for just growth. They’re demanding a clear and sustainable path to profitability and want companies that demonstrate fiscal responsibility and foresight, ensuring that their growth was achieved without compromising financial health. Now, what interests investors is a company that keeps on growing, whilst still making a profit.

If your organisation grows from 20 to 40% but has not achieved breakeven, today, it has no interest to an investor. On the other hand, if a company manages to make a profit of over 10% earnings after costs, and maintain their growth at over 40%, it is considered interesting to an investor.

For that to be achievable, several Key Performance Indicators (KPI’s) are now more important than ever before. It’s no longer just about win ratio or sheer growth. Now, client lifetime value, churn rate, sales efficiency, acquisition costs and retention rates take centre stage for investors. Finding the right balance between growth and cost is imperative and companies now have to show the investment market that they’re able to grow without burning a hole through their pockets. And if, at one time, reaching breakeven was a milestone, it has now become a baseline.

The “attractiveness” criteria have therefore changed. Multiples used to value companies too: today it is rare to use multiples greater than 10, or even 8. After dropping to just over 4, the average is now close to x6, which was the norm in 2016.

But, as with everything in life, there are exceptions to the rule.

The Disruptive Future of AI

With tech companies on the rise and the advent of AI technologies over the past two years, the mindset of investors has shifted dramatically. As evidence, one needs to look no further than to the galloping rise of Mistral AI. In June 2023, this French startup, founded by former DeepMind (Google) talent, Arthur Mensch, alongside ex-Meta AI experts Timothee Lacroix and Guillaume Lample, managed to secure a staggering €105 million in funds, and a valuation of over €240 million. This was achieved just a month after its inception, without even having a product or a website to show for. Such a feat has marked Mistral AI’s seed round as the largest initial seed investment in Europe.

And while some still believe that the best course of action is for a company to grow and achieve consistent profits, some are taking aggressive risks, believing in the long-term potential of these investments. So, in the ever-evolving financial landscape, sustainable growth and profitability are kings, but the allure of disruption is real.

In the ever-evolving financial landscape, sustainable growth and profitability are kings, but the allure of disruption is real.

As we once saw oil or the internet transform industries and become investment titans, we now see a new player on the market, AI, and it seems like everyone wants a piece of it. Artificial Intelligence (AI) has been slowly transforming the market landscape, and over the next few years, we can expect to see a lot of shifting as AI revolutionises the interests of investors.

Moving forward, the private equity sector will have two different playgrounds. On the one hand, investors will stick with the traditional and conservative market approach, where the valuation will be reasonable, and it will be all about profitable growth. On the other, we’ll have this uncharted territory where investors will aim for the companies that promise massive returns, but not without its risks. In this realm, the game is all about spotting the next potential big-thing early on. It’s about placing bets in numerous startups, fully aware that while many will fail, a few could turn out to be the next Meta or Google.

AI has, thus, become more than a technological marvel. It is now an investment phenomenon. And while the market consolidates its rationality and sustainable growth, AI’s disruptive potential will create its own niche.

The private equity landscape has seen a lot of shifts throughout the years, and now more than ever companies need to rise to the occasion and take something out of the lessons of the past. Today, while rapid growth still attracts investors attention, it’s the balance between growth and profitability that ensures longevity and gains their trust.

But still, things can change in the blink of an eye. And whilst today AI seems to have created its own investment ecosystem, you never know what the future holds. Investors and businesses alike must navigate this new era with both ambition and prudence, ensuring that in the pursuit of tomorrow’s potential, the hard-learned lessons of yesterday are never forgotten.

Now, the true question is: will AI-related companies turn into tulip bulbs or Apple(s)? Only time will tell…